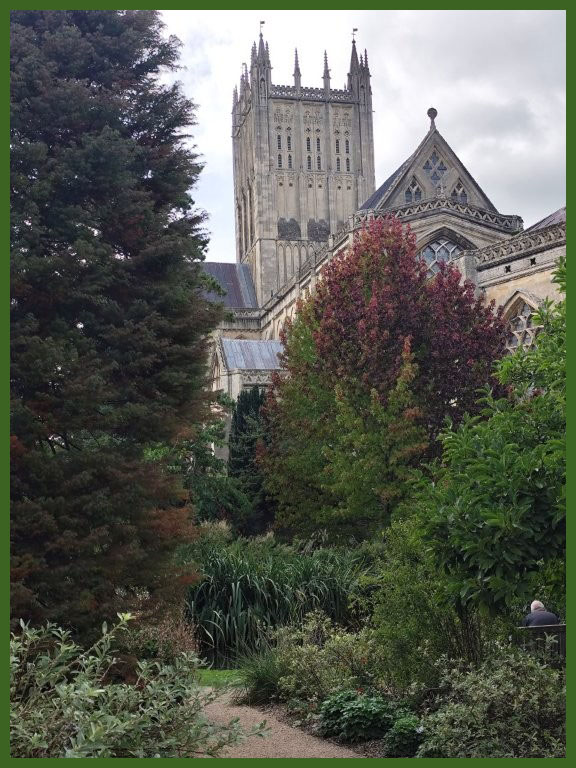

A place of legend where the old and very young find somewhere that speaks to them through ancient walls, colour and design, foliage, or water flowing through the decades: to be glimpsed as a memory at a later age. From the Dean’s Eye, across Cathedral Green then over a draw-bridged moat, we hear of a garden prior to Bishop Jocelyn’s palace and camery, (medieval garden) created early in the 13th century. Later that century the chapel and one of the greatest halls in Europe were built; then a north wing was added to accommodate servants: now offices for the Bishop of Taunton and bicycling Bishop Peter of Bath and Wells, it also being his, his chaplain’s and the head gardener’s home. Late in the 19th century a tennis court existed, the bishop being a member of the lawn tennis association, now used for croquet. Prior to such there were stew ponds and St Andrew’s Stream ran through informal small trees and shrubs as well as the crème del crème of walnuts, a black one.

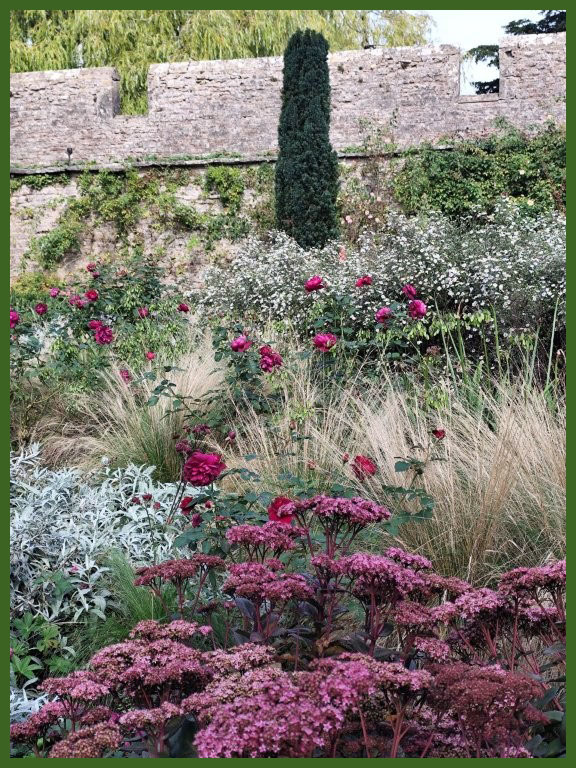

In the 14th century, due an uneasy relationship between the bishop and the citizens, partly due to taxation, the palace was fortified with crenelated (a status symbol) walls. Streams were diverted for a moat, the soil used to construct the ramparts overlooking the medieval deer park: from which bishops have gained solace and spiritual inspiration as well as stocking their larder. Now three gardeners, supported by volunteers, look after fourteen acres within and without and where trees flourish due to a high-water table.

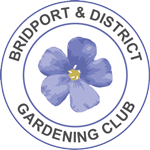

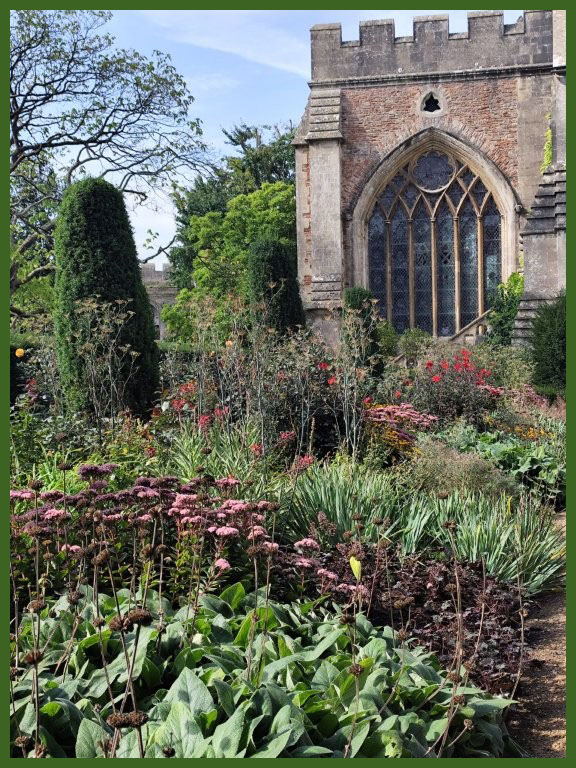

Of the Great Hall only four corner towers and a couple of walls survive the reformation, the roof sold off leading to decay, and the early19th century Bishop Law’s removal of the south and east walls, who wanted a romantic ruin amongst his garden. Later Bishop Bagot removed bricks to create an upper storey for his twelve children. Tons of Mendip top soil were introduced and planted with specimen trees, rose arbours and bedding plants, during WI the garden was repurposed, and as late as WWII there was nothing but a ginkgo biloba tree. Since 2004 the garden has been redeveloped sympathetically to the past by James Cross and his team, with foliage and drought tolerant plants, and in the South Lawn a herb garden where William Turner’s 16th century herb garden existed. There are many trees of note including a tree of heaven, traditionally planted when a daughter is born, and a black mulberry, whose unfurled leaves indicate the end of frosts. A shaded stumpery and fernery with bracket fungus; a long hot herbaceous border across from the parterre garden, with rich foliage scented by old fashioned roses and three bishop dahlias including Bishop Peter Price. Medieval times are reflected by quince and a portcullis design, hedging and conical yews, having been added to the formal Dutch garden in Victorian times, all later filled in during WWI.

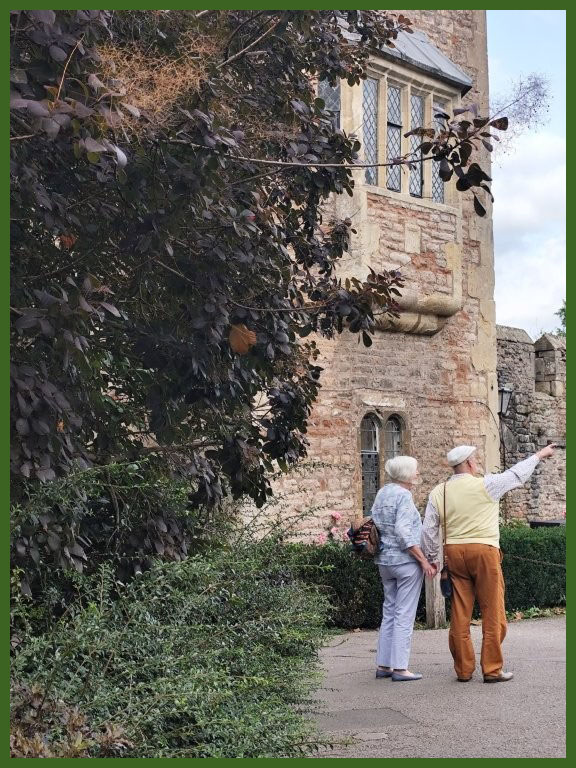

The fortified gardens are left by a yew entwined doorway and bridge, overhung by golden weeping willow, to a mid 15th century well house topped by a bishop’s talbot dog: which provided piped water to the kitchens and fresh water to a conduit for the citizens. Beyond, overlooked by the Bishop windows, is a poignant statue of children, ‘the weight of our sins’, as well as his own gardens fed by a stream from St Andrew’s well. This is in a remote boggy corner known locally as Scotland, an allegorical use for its inhospitable position or due to being ‘scot free’ (tax free), not necessarily the cathedral’s patron saint. The larger well pool feeds the moat via an underground pipe as well as a bridged rill, also the desirable allotments as, apparently, it is easier to get a son into Eton; with heavy rain the water runs cloudy and sluices are opened. A quiet garden of reflection is reached by strolling past the well border created by Mary Keen. Beyond are the community garden and allotments. Within an arboretum, planted to celebrate Elizabeth II silver jubilee and to prevent the council building a car park, there resides a doleful dragon’s lair, a reminder that if the legend is once forgotten he will return every fifty years.

The citizens of Wells may be rightly proud and delight in such gardens, but I must not fail to mention that within the palace is an education in centuries of legend, history and embroidery. The bishop’s chapel, full of light where sunbeams from stained glass cast their colours upon richly carved choristers’ stalls; the pilgrims who have trod their weary way; and the swans who ring for their supper. There is an affecting overview of the gardens at www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-_hydiJ7Lc&t=7s.

Finally, my thanks to our guide Jenny Smith who kindly sent me her notes, Sarah Herring.